Lucie Goux and the Liberation of Etobon

The Etobonais knew that Allied troops were approaching, but they weren’t sure how far away they were or whether they’d arrive in time to save the village. As the Germans departed, they had one last plan to destroy Etobon and its inhabitants. A contingent of fifty German soldiers was approaching the village from Chenebier with orders to burn Etobon. They had already dug holes for mines around the church at Chenebier, where their men had been murdered, and the rumor was that they planned to force the Etobonais into the church and then detonate the mines and burn the building.

One brave villager, Lucie Goux, saved her neighbors by daring to walk towards the Allied tanks coming from Belverne to let them know that the road had not been mined and that they could advance quickly. The Allied troops reached the village before the Germans did, and Etobon was liberated.

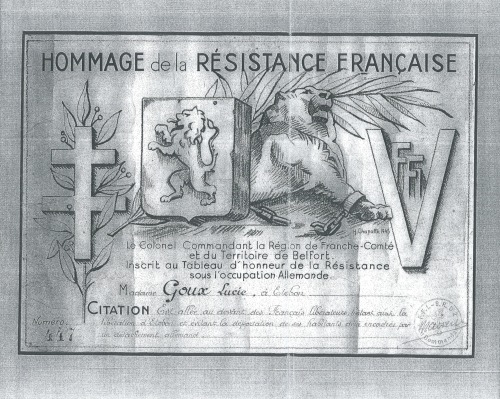

After the war, Lucie was cited for her bravery. Her award is pictured below. The translation is: “Homage to the French Resistance. The Commanding Colonel of the Franche Comté and Territoire de Belfort Inscribes on the Roll of Honor of the Resistance Under German Occupation, Lucie Goux, at Etobon. Citation: she went towards the liberating French troops, thereby hastening the liberation of Etobon and avoiding the deportation of its inhabitants who were surrounded by a German detachment.” The citation is numbered 447 and signed by the FFI Commander.

The first part of Jules Perret’s account of that glorious day:

Saturday, November 18

We get up, really perplexed. A few more boches at the school tying up their equipment on “borrowed” wagons: “bring back right away.” Their cannons have moved out. But the big gun that rings like a bell is still firing.

Around eight o’clock, some girls from Héricourt, who we think are spies, announce they’re going to evacuate us. If only Philippe were in Switzerland! Follow along after the boche wagons? Never. We’re going to head for the woods. Mama prepares a mountain of bundles. Who’s going to carry all that? Impossible. At around 9:30 I decide that we’re staying, we’ll barricade ourselves in the cellar, under God’s care. All of a sudden, Mama’s energy vanishes. She stretches out on the chest at Albert’s and doesn’t move.

A little later, we hear an amazing sound of movement on the Bois de Vaux road. The church bells at Belverne ring with all their might. What emotion! Our liberators? Yes, it’s them! But they would have arrived too late – for the second time – to a village in flames, if it had not been for Lucie Goux, née Bonhotal. She’s the one who saved us. As soon as she heard the bells of Belverne, she set out on foot. Halfway to Belverne, she saw soldiers advancing carefully, sounding the ground with mine detectors. At that rate, it would have taken them 10 hours to get to us, and in two our fate would have been decided. With all her might, Lucie Goux yelled at the soldiers: “Come quick! They’ve left! There are no mines on this road!”

So, they rushed ahead. And, at that very moment, fifty boche were coming from Chenebier with the order to evacuate the inhabitants of the “terrorist village” and to “burn it.” Some even said that they wanted to shut us in the church at Chenebier like they did at Oradour, and blow it up! In any case, the mine holes had already been dug!

Things happened quickly. At 10 o’clock, as I was sitting beside Mama, still stretched out on the chest, I hear shouting. “Here they are! Here they are!” Oh, you who have never experienced a moment like that, you can’t understand! I rush outside, I see two tanks in front of the house, surrounded by a cheering crowd. They weep for joy. They embrace the soldiers. They cover the tanks with chrysanthemums, they toss fruit to them, they hand them bottles. Long live America! The soldiers we’re celebrating seem surprised to find a village with all these people, because they don’t know our story. They’re wearing strange headgear. We ask, crowding around them, “Who are you?” They respond, “We’re French, like you. We’re the resistance from the Haut-Vienne {in the Massif Central, capitol: Limoges}, la Corrèze {in central France, capitol: Tulle}, and l’Yonne {in north central France, capitol: Auxerre}.” New transports of joy, tears, too: “You came two months too late!” “Why?” “They massacred 40 men, all our youth!” We see their faces harden, their fists clench.

After the tanks comes the infantry. Among them, armed and helmeted, five women, very dignified, one whose husband and son had been shot. She can understand us!

At that very moment, there appeared at the corner of the Goutte au Lijon, a little ahead of the others, the advance guard of the fifty boches ordered to burn the village. These seven men, suddenly finding themselves 200 meters from French troops, were so surprised that instead of retreating, they threw themselves in the ravine of the Goutte, where, caught in a rat trap, they became Kamarades. The rest of the band, hiding behind a curtain of trees and seeing their opportunity lost, fled across the fields.

Katherine Douglass

Katherine Douglass